Cha Chinggg! On second thought, let’s kick off the first of this two part Q&A-style Principal & Interest Free Guide to Loans & Lending a little more responsibly. According to the first sentence of The Brief History of Lending (see, I really make sure to do my deep-dive research for you here), “[loans] have been around since the dawn of recorded human civilization”. Unfortunately, since human civilization is long, and blog posts are short, I’ll sadly have to skip most of the history lesson.

I get that it’s not what BenFrank would have wanted, but just between you and me, if you care enough about the evolution of Mesopotamian loan practices, check out the full-length Brief History of Lending here (and then head back, of course). If not, let’s just agree that the loan is an ancient process that hasn’t changed much since the dawn of civilization. So the good news is that once you understand loans and how loans work, you’ll probably not have to revisit any of this for a least another era or two.

Now that we’ve skipped—*er* covered—everything that BenFrank would have wanted, let’s give you the lo-down (*insert pun cringe emoji*) on loans.

What is a Loan?

Actually, since we were all taught this in school already, let’s skip this part too. Sorry, (bi-weekly) Sunday sarcasm! How about let’s be responsible and do what the title suggests, cover the just the basics of loans & lending for you, okay?

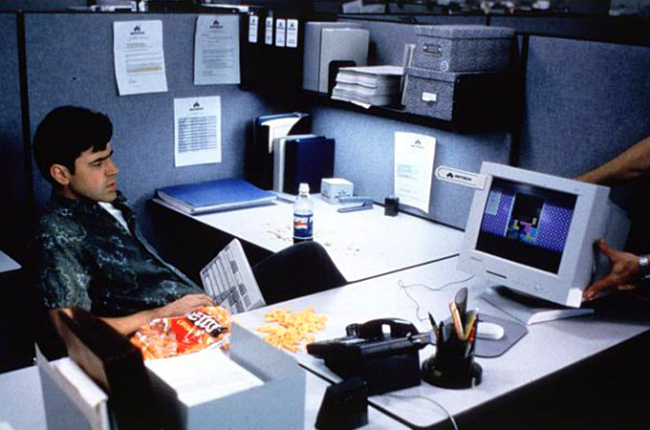

Now let me be Frank. I’ve spent 5 years in a cubicle studying loans and how loans work (part by coercion, part by choice…hence the Office Space image below), but I’ve only taken out one loan myself, to finance my MBA.

However, since unlike Peter Gibbons I only played Tetris sparingly in my cubicle, I’m hoping you give me the benefit of the doubt when I claim that I kind of get the basics of loans and how loans work. With that in mind, in the simplest terms possible, a loan is an agreement between two “parties”—industry parlance for individuals, organization, governments, etc.—to transact over a period of time.

Okay, you say…but this thing transact? Seems like you used one econ-y sounding term to define another econ-y sounding term…

Sorry folks, but welcome to the entire economics discipline! I forget this sometimes, so thanks for the callout. A “transaction”—the nominalized (Gah. Another. Term. Okay, nominalized isn’t econ-y. Just look it up at Dictionary.com if you want to learn a new word)—form of transact is an exchange between two parties at one single point in time.

For a quick example, suppose you stop into Peet’s Coffee and buy your (well, my) favorite black coffee using about two and a half GeorgeWashes. This is a transaction, since you and the cashier both exchange something valuable at a single point in time. At that moment, the cashier, (well Peet’s Coffee) values your $2.45 above its coffee, and you value the coffee above your $2.45. Where there is a mutual agreement like this, a transaction takes place, and neither party owes the other anything beyond a polite thank you. A loan, then, is simply a series of transactions over a period of time.

Hmm okay…But wait, doesn’t a loan involve somebody owing somebody something?

Gah, you caught me again! I was trying to simply. But as AlbertEinst, the intellectual G.O.A.T. (no disrespect to BenFrank) once said, make everything as simple as possible, but no simpler.

So in that spirit, here’s the complete definition of a loan—

A loan is a series of transactions between parties over a period of time, where the payment transactions lag the exchange of the asset (or ownership of the asset).

Wow that sounds boring-y, account-y, AND econ-y. How about a practical example of a loan?

Sure, I though you’d never ask. Well actually, sort of sure. We need to cover a few concepts first. For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume loans have 3 main features—term, interest, and principal—and 2 underlying components—assets and collateral 👇.

The Term, Interest, and Principal

- Term — The duration of the loan. Mathematically, it’s the number of periods (days, months, years, etc.) between the start date—when you owe the first payment—and end date—when you owe the final payment.

- Interest — I promised this was an Interest Free Post, so stay tuned for a future BenFrank Money Post all about interest. For now, let’s call interest simply the cost of borrowing. At first, some people struggle with the idea (certainly me included) that money has a cost. However, since (1) money has time value and (2) you may not repay your loan, lenders account for these risks by charging you interest. Put another way, lenders are providing you a valuable service (literally not unlike a barber/hairdreeser giving you a haircut), so naturally expect something in return.

- Principal — No, not the person who runs a school, like the guy from Billy Madison 👇. The loan principal is the total amount that you borrow (i.e. the full amount the lender writes you a check for) from your lender. Put another way, the principal is the gap between how much you have and how much you need. For instance, if you want to buy a $200,000 house, and have $100,000 to contribute, the principal would be simply $200K – $100K = $100,000.

The Asset & Collateral

- Asset — As defined in my Accounting 101 class (I checked my notes!), any economic good or service that has probable future economic value. For instance, although a candy bar tastes good, it’s not an asset because it has no meaningful resale value and can’t generate it’s own cash (yes, you sillies, even the 100 Grand bars). Instead, things like college degrees, the ability to cut hair, a painting by Rembrandt of Ben Franklin, a steel factory (Philadelphia reference?…crickets?), etc. are all assets because they all have probable future economic value (i.e. there’s a good chance someone out there is currently willing to pay for them).

- Collateral — This one is Level $M, but essential to our level $K (aka Bunny Slopes level) coverage of loans. Collateral is the value of the asset that you offer—either explicitly or implicitly—to the lender in return for the principal. Collateral is important to lenders because in a worst case scenario, they can sell your asset at market value to make back most (or even all) of what you didn’t pay them back. In our house example, the house is the collateral. Seems like, duh right? But trust me, I was in a cubicle studying this for 5 years, it’s not always this straightforward.

Okay, I’m really starting to get it. But aren’t there different kinds of loans out there? Like, I’m applying Min-Max so still drive a 1999 Honda Civic. But of course there are different types of vehicles out there? Trucks, vans, SUVs, etc.?

Precisely, and great analogy you hypothetical person you. I’ll answer that this way. Loans are categorized by the type of collateral that backs them. Take student loans, for instance. Since I currently have a student loan, we’ll go way more in depth on them in a future BenFrank Money bi-weekly Sunday Post, but a student loan is simply a loan that is collateralized by an academic or vocational degree.

Now, you may say, hmmmm, wait a second. How can a degree possibly be collateral. After all, how can a bank “seize” or “repossess” a degree? And who the heck would they sell it to anyway? The Mafia?? After all, isn’t a degree just some fancy calligraphy on a piece of paper with two or three e-signatures on in?

To all this I say, again you’re absolutely right. And you’re starting to discover why people (politicians, economists, lenders, etc.) worry about the $1 Trillion+ student loan debt problem the way they do. This is because, unlike housing, student loans aren’t backed by physical collateral that can be repossessed and resold. That a degree is even an asset represents an implicit bet that the economy will improve, you’ll find a high-paying job, and you’ll make more in the future than the present (i.e. you are an asset, having probable future economic value from your future income). Gah ok, I can’t resist. This brings me to my 5 minute BenFrank Money Soapbox Corner.

The BFM Soapbox Corner

In the United States, we have the privilege (that we often take for granted) of lenders handing us interest-bearing money under the belief that we are mostly good risks. Other countries aren’t so lucky. For instance, in my 6 months in South Africa, I was surprised to learn that only those who can already cover 100% of tuition qualify for federal student loans. Granted, South Africa has one of the world’s most notoriously unequal economies, but this should still help motivate you to not take access to loans for granted.

Flat out, as a US citizen it’s beyond a first-world privilege that I’m able to tell a bank “no I don’t have the money now, but yes I will pay it back in the future”, and still get funded about half of the time. Now wonder why lots of the world STILL wants to immigrate here.

Flat out, as a US citizen it’s beyond a first-world privilege that I’m able to tell a bank “no I don’t have the money now, but yes I will pay it back in the future”, and still get funded about half of the time. Now wonder why lots of the world STILL wants to immigrate here.

Last point on this. I get there are pro-social and pro-community government initiatives help us access our loan markets. And sure, there’s also currently no bankruptcy protection clause in student loans (although I hear politicians are working to change this). However, I deeply believe it’s the historic strength of the US economy combined with the implicit trust with which the US economy operates that gives lenders adequate assurance that 20 year old kids will be able to pay off $100,000 in loans over 20 years*.

*In general, these “bets” have paid off for lenders, as only about 10% of students default (are unable to pay) on their loans.

Unsecured Loans

Okay soap box kicked. Where was I? Oh yeah, a student loan is a great example of an “intangible asset”—something you can’t touch, hold, or repossess—and that has value, such as said degree.

For a non-loan example of an intangible asset, imagine the Nike, Starbucks, or Apple brand. Many of us—yes, even us Min-Maxers—are willing to pay a small premium to buy products from these names, not necessarily because we’re all status obsessed (sometimes true, but turns out to be a popular misconception), but because of the implicit trust we have in these brands to deliver against our expectations.

For instance, I always buy Nike. Why? Well, I believe my Nike shoes won’t break, will be comfortable and high-performance, and, fine, will get me a compliment or two. From my experience, say 19 times out of 20, I’ve been proven right. As a further reinforcement of this belief, when I’ve strayed from Nike into cheaper brands, I’ve been proven wrong maybe 20% of the time. If and (often) when the cheaper brand’s shoes fall apart, I’m stuck spending more than had I bought the Nikes in the first place *face palm emoji*. So now, I no longer take the risk of buying an off-brand shoe. Instead, I pay a little more up front for the “sure thing” Nike sneaker.

In this example, the Nike brand is the intangible asset. The brand name clearly has value beyond the sum of its sneakers, but it’s an abstract quality, so naturally hard to quantify. The same difficult in quantification is true for any unsecured loan. Sure, credit scores attempt to quantify this abstract risk, but are still far from perfect predictors. Because of this, unsecured loans (credit cards, student loans, etc.)―will usually carry higher interest rates than their “secured” counterparts.

Secured Loans

In the other broad category of loans—secured—lenders usually feel more at ease, given they can reclaim the physical asset (house, car, etc.) and resell it at—or near—market value in the event of a default. This partly explains why lenders can offer 30 YEAR TERMS for mortgages (geez, I was hardly alive 30 years ago. Wonder if as a 7 month old infant I could have predicted I’d be at the spot where I’m at, an unemployed part-time editor of a personal finance blog!) at wildly low rates.

Parenthetical jokes aside, it’s malarkey (the good kind) that mortgage rates tend to hover around 3% – 5%, despite the uncertainty surrounding 20+ years into the future. However, it’s mostly because a house (1) tends to appreciate in value over many decades and (2) can be repossessed and resold quickly, that mortgage rates are often so comparatively low.

I’ll stop here..so that’s it for Part I! If you’re feeling energized and would like to work ahead on our Loans & Lending section, head over to How to Calculate Loan Payments Yourself. In instead you’re feeling a little taxed, as my master Yoda/Yogi would say, I highly recommend you to just…wait for it…deep breath…relax (ahhhh, I’ll be so SF for a second…namaste) and rejoin us back here whenever you’re ready.

As always, if you found this Post educational, motivational, or inspirational, please Share it with your friends & fans on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter! Also as always, if you simply can’t get enough great content, make sure to Join our Newsletter or Book a Call with Yours Truly *NEW FEATURE!*